In 1619, a ship docked in Virginia—changing the course of history. On board were some 20 people who’d been captured in southwestern Africa and forced to make the perilous journey across the Atlantic to Jamestown, where they were sold and likely put to work in tobacco fields. They were the first enslaved Africans brought to the English Colonies that would become the United States.

Captive Africans had already been living in the Americas, transported mainly by the Portuguese and Spanish. But many historians point to the ship’s arrival 400 years ago as one of the most consequential moments in history. By the end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in the early 1800s, about 12.5 million men, women, and children, would be taken from their homes in Africa, shackled in chains, and herded onto ships bound for the New World.*

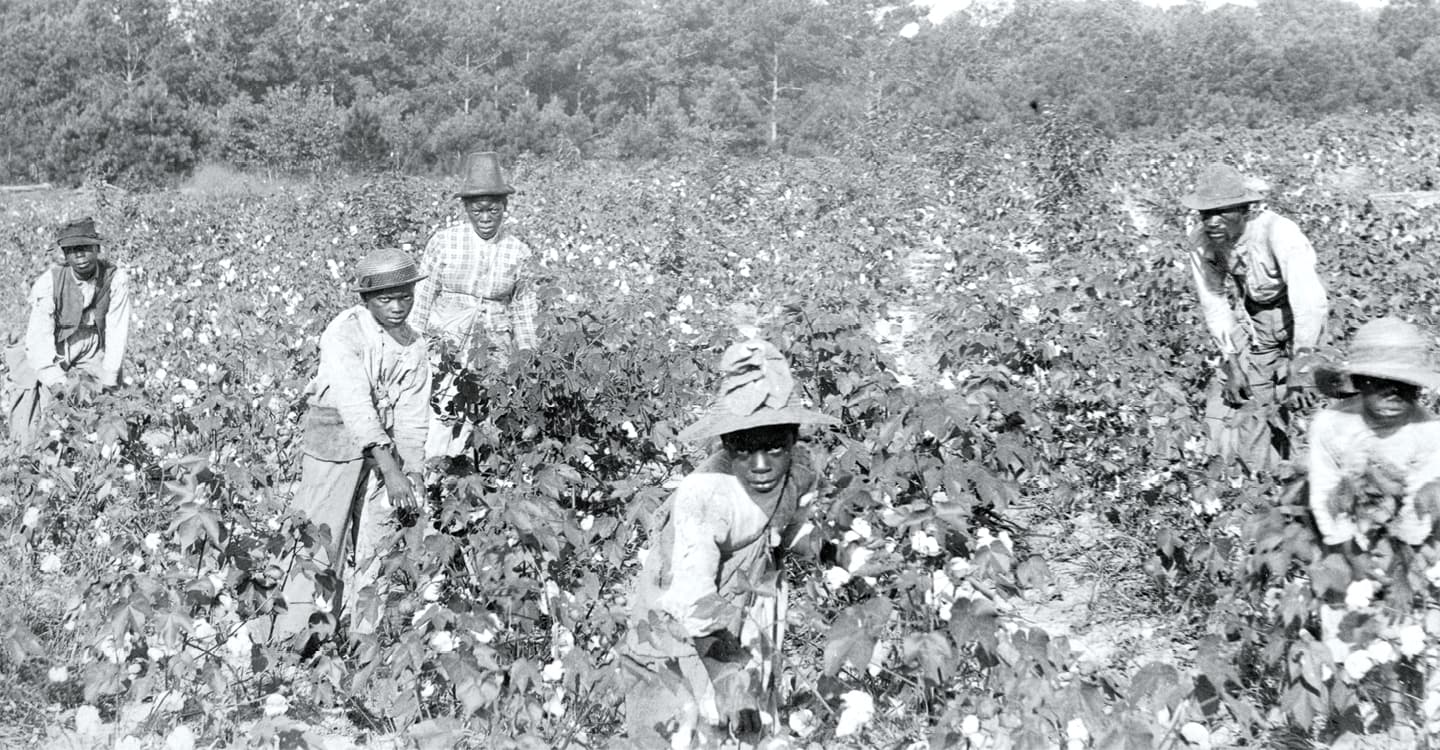

The trans-Atlantic slave trade gave birth to a new form of slavery—one that was based on race, was for life, and was passed down from parent to child. This brutal system of forced labor would propel the colonial economy and fuel the growth of the U.S. into the wealthiest nation in the world.

Yet, despite its impact, many myths about slavery persist. Here are six commonly held misconceptions—and the truth about what really happened.

In 1619, a ship docked in Virginia. Its arrival changed the course of history. On board were some 20 people who’d been captured in southwestern Africa. They were forced to make the dangerous journey across the Atlantic to Jamestown. Once they arrived, they were sold and likely put to work in tobacco fields. They were the first enslaved Africans brought to the English Colonies that would become the United States.

Captive Africans had already been living in the Americas. Most of them had been brought over by the Portuguese and Spanish. But many historians point to the ship’s arrival 400 years ago as one of the most significant moments in history. The trans-Atlantic slave trade ended in the early 1800s. By then, about 12.5 million men, women, and children, would be taken from their homes in Africa. They were shackled in chains and herded onto ships bound for the New World.

The trans-Atlantic slave trade gave birth to a new form of slavery. This type of slavery was based on race, was for life, and was passed down from parent to child. This brutal system of forced labor would propel the colonial economy. That fueled the growth of the U.S. into the wealthiest nation in the world.

Yet, despite its impact, many myths about slavery persist. Here are six commonly held misconceptions—and the truth about what really happened.