For a long time, the mere mention of the word Ebola has been enough to evoke terror. That’s because Ebola is a deadly, contagious disease that has killed—in a particularly gruesome fashion—many of those it’s infected.

But now scientists could be on the cusp of beating Ebola, which has caused more than 12,000 deaths since its discovery in 1976 near the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

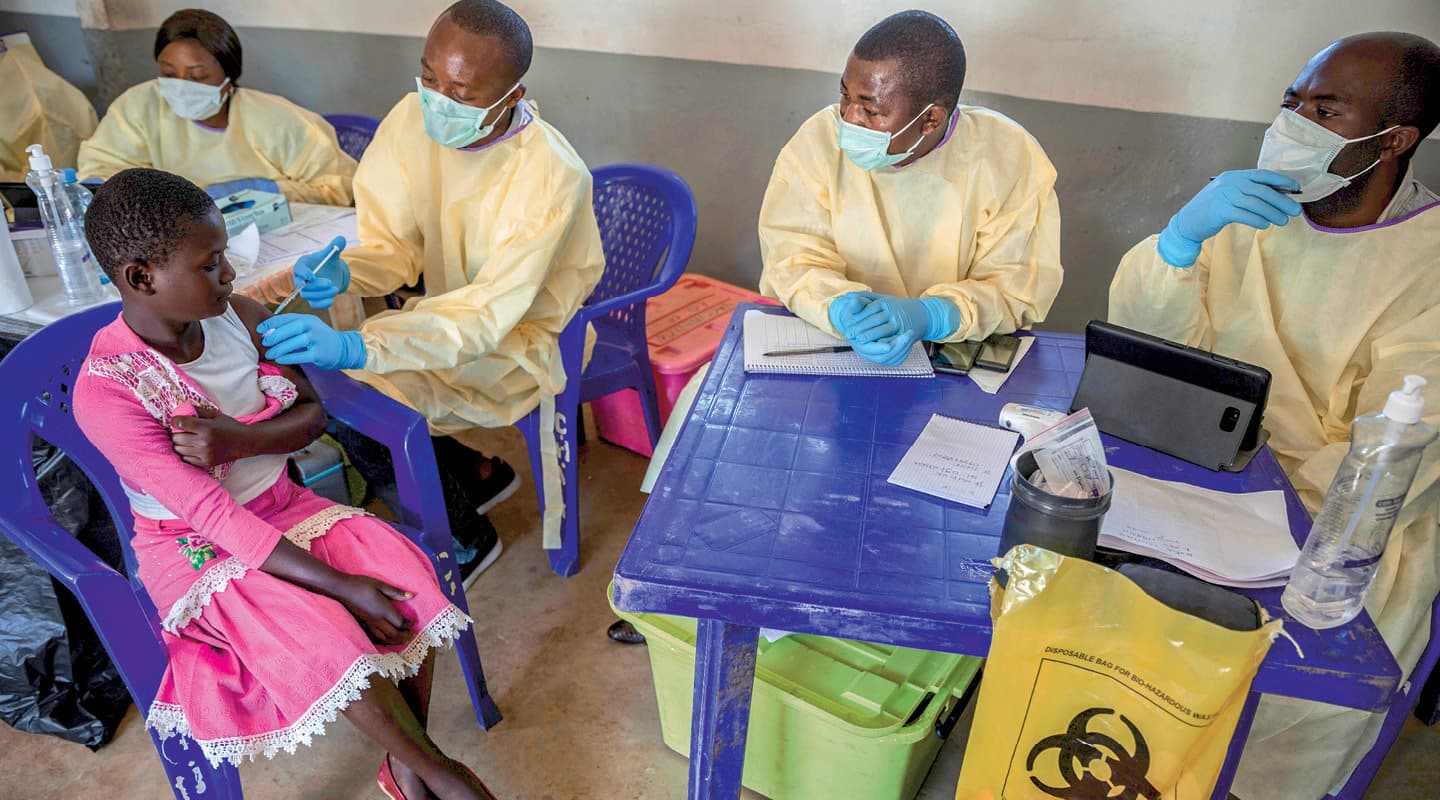

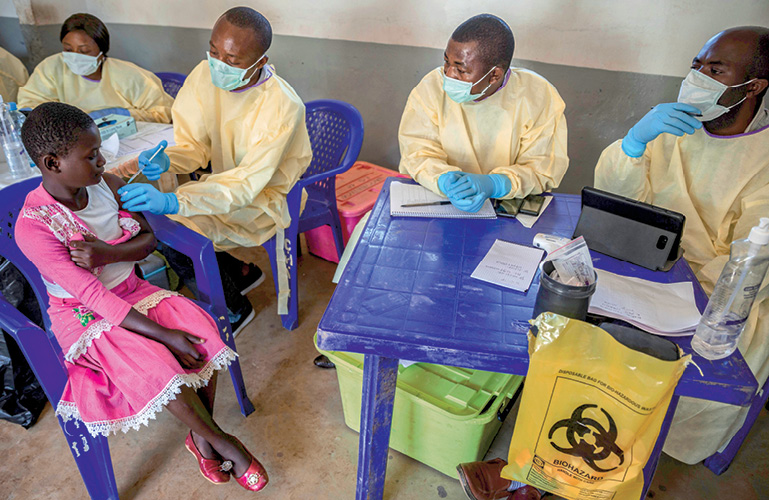

In August, scientists announced that a new experimental treatment seems to work so well—curing 90 percent of those treated—that it will be offered to all Ebola patients in the DRC (see map), where an outbreak has been spreading for more than a year. At the same time, a new vaccine to prevent people from becoming infected—which appears to work 98 percent of the time—is holding out the hope of preventing future Ebola epidemics altogether.

“This totally changes the face of the disease,” says Ashish Jha, who heads the Harvard Global Health Institute. “It’s a reminder that when the world focuses in a certain area, like Ebola, and puts a lot of science and effort into it, we can make amazing progress in very short order.”

For a long time, even the mention of the word Ebola has been enough to evoke terror. That’s because Ebola is a deadly, contagious disease that has killed many of those it’s infected. And it’s done so in a particularly gruesome fashion.

The Ebola virus was discovered in 1976 near the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). It has caused more than 12,000 deaths since then. But now scientists could be on the cusp of beating the deadly disease.

In August, scientists announced that a new experimental treatment seems be working well. It has cured 90 percent of those treated. Now, the treatment will be offered to all Ebola patients in the DRC (see map), where an outbreak has been spreading for more than a year. At the same time, a new vaccine offers the potential to prevent people from becoming infected. It appears to work 98 percent of the time. The vaccine’s success is fueling the hope of preventing future Ebola epidemics altogether.

“This totally changes the face of the disease,” says Ashish Jha, who heads the Harvard Global Health Institute. “It’s a reminder that when the world focuses in a certain area, like Ebola, and puts a lot of science and effort into it, we can make amazing progress in very short order.”